Creating a butterfly garden

Time Allocation: 45 mins *

Activity Level: Easy

Creating a sensory garden

Time Allocation: 45 mins *

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: background

Time Allocation: 30 min

Activity Level: Easy

Creating a yarning circle: site selection

Time Allocation: 45 mins

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: involving First Nations people

Time Allocation: 50 mins *

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: building the yarning circle

Time Allocation: 50 mins

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: connecting to Landcare

Time Allocation: 45 mins

Activity Level: Easy

Creating a yarning circle: using your yarning circle

Time Allocation: 45 mins

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: yarning circle activities

Time Allocation: 45 mins *

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a yarning circle: yarning and wellbeing

Time Allocation: 10-15 mins

Activity Level: Moderate

Local seasons: exploring First Nations weather knowledge

Time Allocation: 40 minutes

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: vision

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: plant list

Time Allocation: 40 minutes

Activity Level: Complex

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: harvesting

Time Allocation: 40 minutes

Activity Level: Complex

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: resources from the bush

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: planting

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden: site assessment

Time Allocation: 30 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Whose Country: exploring First Nations peoples languages map (0-7yrs)

Time Allocation: 30 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Whose Country: exploring First Nations peoples languages map (7-13yrs)

Time Allocation: 30 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Whose Country: exploring First Nations peoples languages map (13-18yrs)

Time Allocation: 30 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Growing your own pizza

Time Allocation: 30 – 40 minutes

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating your own potato chips: growing

Time Allocation: 30 – 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating your own potato chips: cooking

Time Allocation: 30 – 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating your own potato chips: marketing

Time Allocation: 30 – 40 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Catchment management: the story of a river

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Catchment management: water sustainability

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Catchment management: what’s in a drop?

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Catchment management: the drain is just for rain

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Catchment management: where the river meets the sea

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Propagating from fruit and vegetable scraps

Time Allocation: 30 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

Building a nest box

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Caring for our coasts: beach survey

Time Allocation: 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Caring for our coasts: beach clean-up

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Understanding weeds: life cycle

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Understanding weeds: investigation

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Exploring the story of water

Time Allocation: 30 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a wildlife habitat: research

Time Allocation: 30 - 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a wildlife habitat: vision

Time Allocation: 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a wildlife habitat: design

Time Allocation: 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating a wildlife habitat: planting

Time Allocation: 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a wildlife habitat: monitoring and care

Time Allocation: 30 - 45 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a bee hotel: research

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a bee hotel: construction

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Making a large wicking bed

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes* (this will be dependent on site selection and travel time)

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a beneficial garden: assessment

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a beneficial garden: investigation

Time Allocation: 30 -40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a beneficial garden: planting

Time Allocation: 30 -40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating compost

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Investigating the soil food web

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Making a small wicking bed

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a frog-friendly habitat: research

Time Allocation: 40-60 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate, Complex

Creating a frog-friendly habitat: design

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate, Complex

Creating a frog-friendly habitat: construction

Time Allocation: 40-60 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating a food garden: harvesting

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a food garden: planting

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a food garden: installing a no dig garden bed

Time Allocation: 40 minutes

Activity Level: Complex

Creating a food garden: site assessment and mapping

Time Allocation: 30 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Creating a food garden: vision

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

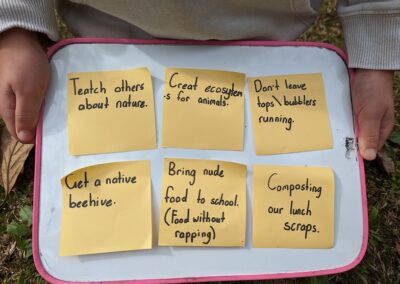

Waterways: behaviour change

Time Allocation: 30-40 minutes

Activity Level: Moderate

Waterways: clean-up

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Complex

Creating a worm farm

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate

Growing healthy plants using natural pesticides

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

Planning a Junior Landcare friendly event

Time Allocation: 40 - 50 minutes*

Activity Level: Moderate, Complex

Soil – more than just dirt!

Time Allocation: 30 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Every drop counts, being water wise!

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes

Activity Level: Easy

Sow a seed, grow a feed

Time Allocation: 30 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

Water for wildlife

Time Allocation: 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

Getting the buzz on bees and other beneficial insects

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

What’s happening in the habitat?

Time Allocation: 30 - 40 minutes*

Activity Level: Easy

Love Letters to the Land

Time Allocation: 45 mins

Activity Level: Easy

Introduction

There are hundreds of different butterflies in Australia. Butterflies need nectar for their adult phase and host plants for their caterpillars. Most butterflies need specific types of host plants that only their type of caterpillar can eat. Before you begin, you will need to research the different butterflies in your area and find out what types of plants will be suitable, as well as prepare your site. Here are some suggested first steps:

- The conservation officer at your local council will be able to point you in the right direction about the types of butterfly in your area as well as what types of plants you can plant to attract butterflies and feed caterpillars.

- Use the Find a Group directory on the Landcare Australia website to get in touch with someone who may be able to help from your local group. They may also be able to help with resources and planting.

- The Australian Museum’s Butterfly and Moth Page

- Your local nursery.

Once you have selected and purchased your plants, you will need to select and prepare your garden bed. Butterflies need both sun and shelter away from the wind, so the best site for a garden bed for a butterfly garden is in a sunny, sheltered spot.

*This will be dependent on-site selection, travel time and having done prior research.

A sensory garden is a garden that invites users to engage with the plants and other features in the space in a way that stimulates all the senses. Choosing suitable and safe plants is important as sensory gardens encourage users to touch, smell and even taste the plants as they participate in the garden space. When planning this activity, it is important to:

- get help from others such as your local nursery, environment group or Landcare group to plan your site

- prepare your site well

- consider how all five senses will be engaged.

In this activity, we suggest that the space is prepared and materials and plants are purchased independently, however you may like to involve your learners in all aspects of the planning, design and planting of this activity. For hints and tips on this process, refer to the Creating a food garden activity series. You will also need to source plants prior to planting out your garden. Your local nursery, garden centre or Landcare group will be able to help give you some ideas about what will grow well in your area. Choose hardy plants that can cope with handling but that also have a sensory benefit, for example:

- long grasses that sway in the wind

- herbs and edible plants that are fragrant such as rosemary, mint and lavender

- plants with different surfaces, such as borage

- plants with a variety of different shapes and foliage colours

- a variety of nectar producing plants that will attract birds and butterflies to your garden.

* This is dependent on the scale of your garden having the preparation of your garden site completed prior to beginning.

Building a yarning circle is a great way to create a space that is inviting and connects children to the outdoors. This space can be used by your class or youth group to yarn about important issues in an informal setting, and to learn more about the Cultural practices and teachings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

For First Nations people, the yarning circle was and still is an important place to conduct business, talk about issues in the community or on Country, and have a space where all voices are recognised and heard.

“We understand that what was spoken in the circle stayed there, unless it was necessary to take any information away like decisions on Cultural practices for another setting,” explains Adam Shipp, First Nations educator and proud Wiradjuri man.

“Our old people would sit or stand barefoot on the earth, on the dirt, which itself provided a healing and safe environment, and our mother earth provided grounding and strength through direct connection. These are practices that can be adopted in our schools today – and will help with mental, physical and spiritual wellbeing.

“We create this area to be a safe place for all; a place where all people have a chance to yarn on equal terms.”

Establishing a yarning circle in your school or community also provides an opportunity to create an outdoor learning space that will help immerse children in nature. We often think of nature as being separate to us; out in the ‘bush’ far away from our towns and cities. However, when you take the time to sit and observe everything around you, you will soon start to recognise the scents and colours of the trees, plants and flowers in your school; the sounds of the birds that visit those plants; and the insects that many of those birds and smaller animals will feed on. You may be surprised at just how much you can see, smell and hear just by sitting in your yarning circle or outdoor area.

Now that you’ve decided you would like to set up a yarning circle in your school or community, it is important to figure out where to place your seating area. Important things to consider include:

The physical area or location:

Seating:

Visibility and accessibility:

Once you have gone through the important considerations above, you can start thinking about how to design your yarning circle space to bring it to life.

The next learning activity ‘Creating a yarning circle: involving First Nations people’ will provide tips on how to get the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community as well as the broader school community involved.

It is important to think about how you might work with the local First Nations community. Considerations include:

Try to invite and incorporate First Nations’ voices and opinions from the very start of the project so that it is carried out as respectively and cooperatively as possible throughout.

You can research service providers for gardens and landscaping on websites like Supply Nation, which is a site set up to promote First Nations businesses in many different fields.

Does your school have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students who would like to get involved in the project? They may have an idea about the design. Maybe they would like to design other cultural elements for the yarning circle or incorporate a special animal, plant or artefact that is important to them.

This may also be a good opportunity to incorporate a traditional story of the area where you live, working with the local Custodians and Elders. Keep in mind, their time is precious and you will need to have budget set aside for their time and assistance. If you need to purchase any items, such as a talking stick, to help your yarning circle operate, make sure you let them know early so they have time to prepare or help source materials.

For educators, Landcare facilitators or students starting the community consultation journey who feel they may not know where to begin, our advice is start talking with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families connected to your school. There may be an Indigenous Learning Officer or similar type of staff member in or connected to your school who could give you advice about working with/connecting with families of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. If such a role does not exist at your school, then reach out directly to families of/other students. Even if they do not have exact information on how to set up a yarning circle themselves, they may be able to connect you with Elders and/or community members who do have skills and knowledge to help you.

* This will be dependent on drafting and other aspects of the task

This is an exciting stage of the project when you can start to think about HOW you will build your yarning circle. There are many things to consider here, for example:

What materials will you use for the seating circle?

Wood and stone are often popular choices as they will help to maintain a natural look and feel for your space. Always remember, however, that a yarning circle can be as simple as sitting down in a circle, on the ground or with cushions, and that having a large budget is not necessarily a constraint.

What is your budget?

Sandstone or professional wooden seating can cost anywhere between $5,000-$15,000, depending on how much labour, time and quantity of seating is required. If this is outside of your budget, you may need explore other options. For example, in urban and regional areas where there is lots of development/construction work going on, you could reach out to developers or construction companies, councils, etc. to see if they are getting rid of any materials, such as large stone pieces or wood, that could be donated to your school instead of going to the tip.

What cultural considerations do you need to bear in mind?

There may be traditional customs and beliefs when it comes to natural materials being removed from/introduced to Country. Where possible, your choice of material should be done in consultation with Traditional Custodians and First Nations community representatives. This applies to the use of more conventional materials like sandstone too, as it may not be a natural part of the landscape you want to bring it to.

1. Consult with the local First Nations community about the location, design and best choice of materials to use.

2. Speak with local businesses (preferably First Nations businesses) about quotes for materials, construction of the site, etc.

3. If your budget is small, reach out to your local council or developers/construction businesses in your area to enquire about material donations. Local business may also be willing to donate time to help construct/install materials. You can also look for grants and connect with your local Landcare group for guidance or ideas on available grants.

4. If you are not using a professional construction/landscaping company to install your yarning circle, set up a community or parent working bee with volunteers who have experience in this area.

Remember, there will be important safety considerations when building the yarning circle e.g. the operation of machines (bobcat, etc.) to shift heavy materials into place and making sure seating is fixed securely and won’t move or roll over, potentially causing safety issues.

In this activity you are going to connect with your local Landcare or other community environment group. Working with your local Landcare or environment group is a great way to access local expertise, support and resources.

Connecting with Landcare can occur at any time during your yarning circle project, from the initial phase when you are selecting your site to set up your yarning circle to enhancing the area around your yarning circle once it has been established.

Landcare doesn’t always need to be a hands-on activity. Immersing children in a yarn or conversation is a great way to build their understanding and awareness of different cultures, landscapes and why it’s important to care for their environment and our natural resources.

Having a yarning circle in your school is also a great focal point for understanding the intricacies of your local landscape, connection to culture and connection to Country. It provides a space for many tangible and intangible connections that you can draw to enrich learning experiences.

You did it! Your yarning circle is now complete. It looks extremely inviting and has become a central point of attraction within your school. The question now is, how and when do you use it?

The main thing is that it does not just become a token gesture and space that isn’t well utilised in the school. A yarning circle can be used as a teaching and learning space for your everyday classes, when sharing and discussion is an important focus of the lesson.

When to use a yarning circle:

A yarning circle can be used whenever you need to have a chat, share or mediate. In a school setting, it could be used when:

You may wish to hold smaller intimate circles on regular occasions (for example, once a week) and then plan to hold larger ones where an Elder or First Nations community member/s are invited into the space, if/when possible.

Talking sticks:

This activity also introduces the concept of a talking stick. The stick symbolises your turn to have your say; when others should respectively listen to you before having their turn to speak with the stick. The yarning circle can continue until everyone has had their turn to speak, be listened to and voice any concerns or opportunities they wish to pursue. This will embed an important practice and safe space for all students so they feel comfortable sharing.

There are many different activities that can take place in your yarning circle. Yarning circles provide opportunities for all to be heard, for discussions to be had and for understandings to be reached.

This series has been created to help ensure your yarning circle is used regularly; and is a space that staff and students alike want to return to again and again and can be incorporated into existing activities or to inspire new ones.

The planner created in this Learning Activity should be displayed in a central location, such as the staff room or main entry, to remind teachers about the yarning circle and the various things that can take place there.

This activity also draws upon the Local Seasons: exploring First Nations weather knowledge Learning Activity in the Learning Centre.

* This is dependent on having already completed the Local Seasons: exploring First Nations weather knowledge Learning Activity, and pre-work such as a list of activities and dates compiled.

In this learning activity we explore how yarning circles can be used for wellbeing based on the morning circle routine. However, there are many other ways you can use your yarning circle for wellbeing activities, for example, for dispute resolution, restorative practice and cultural sharing.

Being outdoors tends to allow us to slow down and reflect. A well set-up yarning circle can provide a welcoming atmosphere and can be utilised as a safe space to talk, share, discuss and have a yarn together; a place to build respectful relationships and enrich not just students' learning experiences but their overall sense of wellbeing in a natural setting.

It's also a great place to invite First Nations community members to share more about their Culture and run cultural activities like weaving, stories, Indigenous plant use and bushfood tasting, even cooking if the amenities are available; the meditative practice of weaving, art and cooking can also have positive effects on mental health.

Finally, providing First Nations students with an opportunity to showcase their Culture is an important way to create a better understanding of self and identity, which is a powerful tool in improving wellbeing; whilst exposing non-Indigenous children to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultures is an important way to develop respect for diversity and Traditional Cultural Knowledge.

This activity introduces children to going outside and experiencing the seasons.

First Nations people observe the seasons change and they know when it is best to collect food such as fruits or seeds, what type of shelter they would need to make, what clothing they would need to keep warm and when to move from one place to another.

To understand local stories and support these activities, we recommend reaching out to your local Traditional Owners and First Nations peoples community groups, who can assist in knowledge sharing and understanding local land, histories and culture.

Planning this garden starts a journey of understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and histories, and towards reconciliation. It is a wonderful opportunity to create a space to pay respect to the First Nations peoples of Australia and their extensive knowledge of the plants that grow naturally in the Australian landscape. The garden you will create will be a space that educates not only your group, but many children and adults for a long time to come.

Your vision, and collaborative and consultative planning is an important part of this project. Growing your garden will grow your understanding and strengthen your relationships with First Nations peoples.

For thousands of years, First Nations peoples across Australia have been planting and utilising a diverse range of plants. This learning activity will introduce our learners to a range of Australian plants and explore the multiple uses that each plant has for First Nations peoples.

This activity will help set the foundations to creating and understanding the importance of Indigenous plant-use and creating a garden, and help select plants to include in your Indigenous plant garden.

Creating an Indigenous plant-use garden is usually different to common vegetable gardens as these plants will require different growing conditions.

Harvesting your native produce will not only provide the experience and joy of growing your own edible plants, but also provide a deeper understanding of First Nations peoples culture and histories.

This activity explores the importance of plants for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who know and understand the plants, life cycles, seasons, and the different ways plants are used. Care must be taken when interacting with plant materials. Correct plant identification is crucial to knowing which plants are edible and which are best to avoid.

This is a great opportunity to invite your local Traditional Owners take you on a guided walk so they can share their deep knowledge, connection and understanding of the land, stories and culture specific for your area. This is also a great way for starting to build relationships with your local First Nations community for the future, and take action towards reconciliation. Growing your garden will grow these partnerships even further.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Learners may visit bushland or look at native plants in the school garden, local park or reserve.

Planting an Indigenous plant-use garden is a great way to learn about the importance of native plants to First Nations peoples. It is also an easy way to expand your diet in a way that incorporates foods that are native to this land and have been used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for a very long time. The health benefits of these plants are becoming more widely understood so it is important for all Australians to start incorporating these foods in their cooking. Of course, many of these foods are extremely tasty as well!

Inviting the community to plant with the children is another opportunity to build relationships with the local First Nations peoples community (as well as other stakeholders in the school community such as parents and carers).

Prepare your garden area before planting. Refer to the site assessment learning activity to create the best conditions for your plant use garden.

*The time allocation for this activity is based on all materials being sourced prior to commencing the activity.

Assessing a suitable site for your Indigenous plant-use garden is important. It can be the difference between developing a successful thriving garden or creating a place that has constant ongoing issues.

In this activity, we will be assessing local areas so to locate the best site for an Indigenous plant-use garden. Working in teams will help build skills for working together in the development of the garden and foster self-reliance.

*Time allocation is dependent on site selection and travel time.

As children learn to acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the traditional custodians of lands, waterways and skies across Australia, it is important that they recognise that Australia is home to hundreds of many First Nations communities.

This activity introduces children to a First Nations languages map and builds understanding and appreciation of the importance of language to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity and culture.

This activity introduces children to a First Nations peoples languages map and builds an understanding and appreciation of the language and culture of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Adam Shipp a Wiradjuri man shares the following:

“Language is a part of everything we do. It is in our country, our rocks, trees and landscapes. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people it is important for us to connect and reconnect to language of our ancestors and to speak this language every day. We believe our ancestors are always watching over us, so to speak our native tongue is to connect directly to them.”

Adam Shipp a Wiradjuri man shares the following.

“Language is a part of everything we do. It is in our country, our rocks, trees and landscapes. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it is important for us to connect and reconnect to the language of our ancestors and to speak this language every day. We believe our ancestors are always watching over us, so to speak our native tongue is to connect directly to them.”

In this activity, children are going to investigate what they would need if they were to grow their own pizza. This activity is designed to help young learners explore food production and how something seemingly simple, such as a pizza, uses ingredients from many different origins.

Before beginning this activity, gather the materials needed to ensure that the learning outcomes can be achieved. More information is available in the Educator Notes.

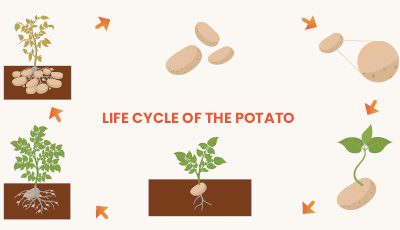

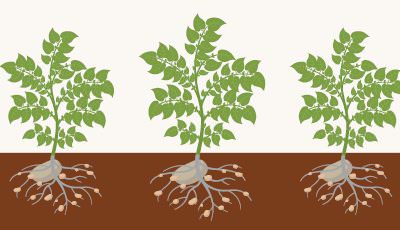

In this activity sequence, children will investigate what would be required to grow, cook and market their own brand of potato chips. For simplicity, we are focusing on the ‘hot chips’ style of potato chip, rather than ‘crisps’.

The process of growing the potatoes takes many months, but children will be rewarded with a wonderful crop at the conclusion of this exercise. We suggest combining this activity with gardening activities such as the Creating a food garden series to help provide the resources and materials needed to produce a crop of potatoes.

* Time allocation reflects the time suggested for learning about potatoes, planting them and completing the activity sheet.

Growing food for your own table is very satisfying. In this activity we are taking the concept of growing food one step further, to turn it into a product.

Children will use the potatoes they have grown to create their own potato chips. For simplicity, we are focusing on the ‘hot chip’ style of potato chip, rather than ‘crisps’.

The intention of this activity is to provide children with knowledge about food production, the timelines and other inputs involved in producing a crop. Ideally the potatoes that the children grow themselves should be used for this activity, however if this cannot occur store-bought potatoes can be substituted.

We suggest that you run this activity as part of a kitchen garden cooking activity.

* Time allocation reflects the time suggested for harvesting, cutting and preparing the chips. Cooking time may be additional depending on availability of oven space and temperature.

Growing food for your own table is very satisfying. In this activity sequence, we are taking the concept of growing food one step further, to promote the produce that the young learners have created.

In the first and second parts of this activity, children grew potatoes and turned their produce into hot chips. In this final sequence, the young learners will consolidate their understanding of food production by creating an advertisement about their chips.

The story of a river learning activity investigates the journey of water through the catchment, from the mountains to the sea. Fresh water is a finite resource and is essential for all land plants and animals to survive. Explore the competing demands for water in a typical catchment.

*Adult preparation for the activity 20 minutes

This water sustainability learning activity investigates the different uses for water across a catchment. Within a community, stakeholders can have different opinions on how water should be shared. Explore these competing demands for water in a typical catchment, and discover ways of being more sustainable.

*Time allocation includes 15 minutes of pre reading the case study resources.

This learning activity explores urban water consumption and waste water. Conduct a water audit at home or school to discover where water is wasted in your life and what you can do to save water.

This activity investigates the journey of water into the drains. Most rubbish, especially plastics, enters our waterways through stormwater. Explore your school or local area find out what is going down the drain.

*Time allocation includes adult preparation of 10 minutes for the activity.

This activity investigates the journey of waste into our waterways and eventually the sea. Students explore how waste can impact our wetland and marine environments.

*Time allocation includes 20 minutes of adult preparation.

Growing plants is a great way to introduce their features to young learners. In this activity you will be using fruit and vegetable food scraps that might have otherwise been discarded, to regrow or sprout new plants. A great way of engaging young learners in science is to encourage them to observe the new shoots and monitor how they grow and change over time. You will need to have your materials ready before you begin, so that the activity runs to the allotted time. This activity can be integrated with a cooking activity or aligned to a collection of fruit and vegetable scraps, so that resulting plants are produced authentically. *Time allocation will be dependent on having materials already prepared.

Many of our native animals need tree hollows to shelter and raise their young. Deforestation, competition from introduced animals and urbanisation has resulted in less hollows being available for native wildlife. Nest boxes are a great way to re-create habitat. This learning activity is designed to help educators and young learners successfully complete a nest box project.

Building nest boxes from scratch is a complex activity, using specialised tools and equipment, so we have given some pointers in this activity to make this more simple and achievable. There are many things you will need to consider when making a nest box, so we suggest getting in touch with your local landcare, environmental group or local government before beginning, as many of these organisations hold specialist knowledge about your local animals and can often help with resources and expertise.

*Time allocation is based on having prepared materials and research completed prior to commencing this activity.

This learning activity investigates microplastics, where they are found and how they end up in our coastal waters.

*Time allocation does not include travel time to the beach and coordinating the groups and equipment.

This learning activity explores the impacts of microplastics on our marine environments.

*Time allocation does not include travel time to the beach and coordinating the groups and equipment.

Weeds can look like any other plant, and can often even look very attractive.

However, a weed is a plant that grows where it is not wanted, and they are very successful in their reproduction. Learning about the life cycle of weeds can help us control and manage their spread, and understand the impact they have in the local environment.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Investigating weeds in your local area and reaching out to local experts like Landcarers and council staff can help to build identification skills and become a Weed Warrior champion. Because our precious environment is threatened by invasive garden plants and weeds that take over large areas of bushland and evict native species, being skilled in identification and management of weeds is important for the health of your local environment and biodiversity to reduce pressure on fragile ecosystems.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Water covers 75% of the earth’s surface; only 1% is available as fresh water. Freshwater is essential for all land plants and animals to survive. The story of water learning activity investigates the journey of water through the environment, from the mountains to the sea.

*Adult preparation for the activity 20 minutes

Creating a native wildlife habitat is a great way for kids to discover what is living in their backyard and local area. Not only will children learn about plant and animal species, they will understand the importance of urban habitats. The research phase is essential to discover the animals that already call your garden home.

We encourage our Junior Landcarers to learn more about wildlife habitats by exploring these other learning activities. These include the Creating a frog-friendly habitat sequence: research, design and construction, Creating a bee hotel sequence: research and construction as well as Building a nest box.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or native plant nursery.

Having an understanding of the needs of native animals in your school or local area will help build a connection to place, and help to get support from your community to a create a wildlife habitat. This activity enables children to appreciate the diversity of local native animals in the community and understand how to protect them.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or native plant nursery.

Creating a wildlife habitat helps you create an environment that will ensure the survival of local animal species. The design phase is essential to ensure your wildlife habitat will meet the needs of the native animals that already call your local area home, and encourage more species to live in your new wildlife habitat.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or Indigenous plant nursery.

Planting is a great way to learn about the importance of native plants in creating habitats. Children will learn about the best location and conditions for native plants. The planting stage is where the children will be applying the information discovered in the research, vision and design activities already undertaken in this sequence. This will help establish a garden that will provide food and shelter for local native animals all year round.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection, travel time and that site preparation has been completed. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or native plant nursery.

What happens now that you have finished creating a wildlife habitat? The monitoring and care phase is important to ensure all your hard work isn’t washed away, and that your plants are healthy and growing well. It is also a great way to find out if your wildlife habitat is a success, and providing a home for local wildlife.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or Indigenous plant nursery.

Before embarking on this learning activity, we encourage our Junior Landcarers to learn more about beneficial insects by doing the Creating a beneficial garden activity series to further provide our young learners the opportunity to learn more about invertebrates, focusing on pollinators and beneficial planting. This will help our young learners understand the importance of this activity and build their commitment.

Upon completion of this learning activity, children will have developed a deeper understanding of bees, including their identifying features and native habitat so that they can help protect them.

*Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council or Indigenous Elders.

Before commencing this activity, the Junior Landcarers are encouraged to develop a better understanding of bees, their features and their native nesting habitat. Learners will apply prior learning and information gathered to identify the things to include in their bee hotel, to best mimic the bees’ natural habitat.

This activity will require adult supervision and some ground work to gather materials. We suggest connecting to your local Landcare group or hardware shop, as they may help provide some of the materials.

*Time allocation is based on all materials being sourced prior to commencing construction.

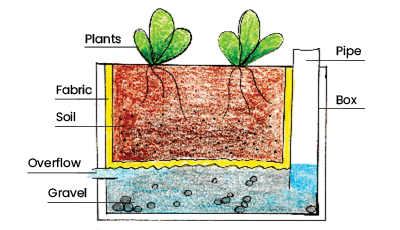

Wicking beds use a water reservoir and the capillary action of soil to supply water to plants from below, and can be built from a variety of different materials. The bed featured in our learning activity is made out of a halved IBC tank, but they can be made out of an old bath, halved barrel, upside-down fridge or some other vessel. Constructing the wicking bed explores a range of sustainability concepts including water use, land use, reusing materials and technology in food production.

Making a large wicking bed is a great way to save water and grow a productive vegetable garden, and can often be found in kitchen gardens, household vegetable patches and learning centres. This activity does involve a few key steps, and requires adult supervision to ensure that the sequence is successfully followed.

*The time allocation for this activity refers to the building of a wicking bed, with all materials prepared and ready to be installed. Preparation details are included in the Educator Notes. Sourcing and preparing the materials prior to commencing the activity is essential to successful completion of this activity within the allotted time. You will need extra time again for planting.

We’re going on a bug-hunt! A ‘bug’ is the broad term given to an invertebrate animal (animals without a backbone). Many different invertebrates visit gardens, or call them home. In this activity, you will be completing an assessment of the types of invertebrate in the garden. They could range from worms that break down organic matter, to bees that pollinate flowers, or even pest animals that eat crops, such as snails and slugs. This activity is designed to provide the knowledge and tools for other learning activities in this sequence.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

The aim of this activity is for our young learners to make the connection between beneficial insects in the garden and their relationship to flowering plants. Invertebrates or bugs that provide services such as pollination or pest-predation are commonly known as beneficial insects. These insects can often be encouraged into a garden by planting flowering plants alongside food crops. This is known as beneficial gardening.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Planting flowering plants next to a food crop is known as beneficial planting. The flowering plants (beneficial plants) attract pollinators and predators, which help increase your food crop and protect plants from pests. In this activity, children will be applying the information discovered in the assessment and investigation learning activities already undertaken in this sequence. This activity provides opportunities to apply learning, test hypotheses and monitor progress.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

There are many different ways to create compost. This activity has been designed with the needs of the educators in mind and employs a simple method of composting. Before beginning this activity, it is important to gather the materials required, including the compost bin and a mixture of ‘green’ and ‘brown’ materials. Selecting an appropriate site for your compost is also important; choosing a site with good shade and direct contact with the soil is necessary for your compost to work.

We encourage our Junior Landcarers to learn more about soil by exploring these other learning activities: more than just dirt, soil food web, creating a worm farm, and the installing a no-dig-garden bed activities.

*The time allocation is based on materials being sourced prior to commencing construction.

In every square metre of soil, there are millions of organisms. These organisms make up the soil food web. The soil food web recycles nutrients in the soil, making them available for plant growth. The concept of the soil food web may be very new to children and educators alike. This activity is designed to facilitate a hands-on exploration of some soil samples to find evidence of the soil food web.

Preparation of equipment and resources prior to beginning the learning activity will help to make it a success. Access to magnifiers is helpful because some of the organisms are quite small. If magnifying glasses are not available, using technology such as the camera on phones and tablets can be a good substitute and there are a number of apps that allow these cameras to be used in macro mode.

*Time allocation is dependent on site selection and travel time.

Making a small wicking bed out of a polystyrene box is a great way to upcycle materials to produce a functional planter-box, providing participants with a great sense of satisfaction. This activity does involve a few key steps, and requires adult supervision to ensure that the sequence is successfully followed. The water saving features of wicking make this small garden bed ideal for food plants such as herbs, vegetables and berry plants.

The small wicking bed is a great team-building activity, and more than one bed can be produced by older students working in small groups. This activity involves many roles to maximise student-participation and introduces scientific ideas that can be further investigated. When completed, the wicking bed may be deceptively heavy (a standard polystyrene box filled with soil could weigh around 20kg)and awkward to move, so it is best to build the bed in its final location.

*The time allocation includes preparation details included in the Educator Notes. Sourcing and preparing the materials prior to commencing the activity is essential to successful completion of this activity within the allotted time.

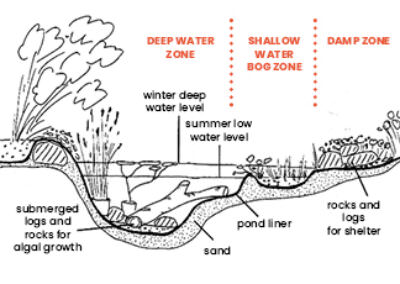

Most young learners will come with some prior knowledge of frogs. Upon completion of this learning activity, they will have developed a basic, moderate or complex understanding of a local frog’s specific survival needs, depending on their stage of learning. The research and planning phases are essential to creating a suitable frog habitat.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time. Additional time may be spent in consultation with your local Landcare group, council, or indigenous plant nursery.

Before constructing a frog-friendly habitat, young learners will be required to create a design or a plan. Learners will apply prior learning and information gathered during the research phase to identify the things to include in their habitat design. Having a sound understanding of the frog’s specific survival needs is essential to designing the frog-friendly habitat. The habitat will be created with both living and non-living elements. The design must be fit for purpose.

*The time allocated is to create a cross section design of the frog-friendly habitat, providing the research phase has been undertaken prior to commencing.

There is a comprehensive list of safety and planning considerations, and materials to gather before commencing the construction of a frog pond. Please refer to the educator notes via the button above. Before commencing this activity, the Junior Landcarers will have already created a habitat design, informed by their research to guide this next construction phase of the project. This activity will require adult supervision and some ground work to prepare and move materials. Adequate preparation of materials beforehand and following safety instructions are vital. Having several volunteers to contribute and help when others need a break will ensure this is an effective and efficient activity.

*The time allocation for this activity is based on all materials being sourced prior to commencing construction. Most of the construction materials can be sourced from a local hardware store; and the native aquatic plants and shrubs from a local indigenous plant nursery. It is difficult to advise on how long it will take to dig the pond hole - as this is site and soil specific.

Harvesting your produce at the right time will enable you to get the most out of it and ensure that you can reduce waste. Experiencing the value of growing your own edible fruits and vegetables and then sharing with the wider community, builds active, empowered and aware Junior Landcarers. This helps to build awareness of sustainable food production.

Planting seedlings is one of the most satisfying tasks as it helps to bring your food garden to life relatively quickly. Understanding the best location and conditions for your plants, taking good care, and documenting what you plant will help to grow a productive garden. Advance preparation of your garden bed, being ready with suitable plants, and working in teams will help this be an effective and efficient activity.

Being involved in making a no dig garden is a great team building activity, it helps to establish plants very quickly without having to do heavy work of digging out a garden bed. As there is minimal disturbance of the soil layers in establishing this garden bed, it does not disturb existing soil life.

This activity will require adult supervision and some ground work to prepare and move materials. Adequate preparation of materials beforehand is important and safety instructions are essential. Having several helpers to contribute and fill in when others need a break will help this be an effective and efficient activity.

The time allocation for this activity is based on using a small garden bed space of about 2 metres by 1 metre. Larger areas will require more time, materials and assistance.

It would be ideal to have equal amounts of green and brown materials to layer in the garden bed.

In this activity we will be getting to know our own grounds so that we can locate the best position for a food growing garden. Working in teams will help build skills for working together in the development of the food garden.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Planning a food garden can be a very exciting and beneficial process to keep you healthy and engaged in the great outdoors. Get started with planning and creating a vision for your new food garden. Creating a vision for your garden will help it be on a pathway to success by reflecting on the purpose and assist in the steps to get the best possible benefits. Most young learners will come with some prior knowledge of food gardens. Upon completion of the activity they will have considered important aspects of developing a food garden as well as their vision.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Water quality is important to the liveability of places for people, animals and vegetation. If everyone makes small changes, we can make a big difference to the health of our waterways. Junior Landcarers will be able to draw on their experiences from their waterways clean-up activity, field data collection and analysis, to identify ways they can personally adjust their habits to reduce their waste and influence others to do the same.

Junior Landcarers on their own or working as a team, can clean-up waterway to make a visible difference and help improve ecosystems. From picking up rubbish to collecting and analysing data, they can identify the ways people can help reduce waste and protect water supplies.

Adequate preparation of materials beforehand is important and safety instructions are essential. Please refer to the educator notes for a comprehensive list of safety and planning considerations, as well as materials to gather before commencing your waterways clean-up and data collection.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

An activity idea before you construct the worm farm, you may want to invite the young learners to form small groups and create a labelled cross-section drawing detailing the layers of the worm farm, this will help them understand the construction process. The young learners will need to have sound understanding of the purpose of a worm farm and the earthworms’ specific needs before commencing the worm farm construction. This activity will require adult supervision and some ground work to prepare the materials. Adequate preparation of materials beforehand is important and safety instructions are essential. The time allocation for this activity is based on constructing one worm farm.

*Time allocation estimate if all materials have been previously sourced.

Having healthy plants is dependent on a variety of factors. Before commencing this activity, be sure to identify the pest species on your plants. Certain pesticides are only suitable to treat specific pest species. The natural pesticide featured in this learning activity is to treat sucking pests such as aphids and scale.

*If all materials have been previously sourced.

With Australia’s growing population, we need to find solutions to manage our waste produced from food production, gardening, leisure activities, technology and general goods. We need to divert waste from landfill that can be reused, recycled or composted so that valuable resources can be recovered. Landfill is the name we give to the rubbish or waste that is buried, sometimes known as a tip or rubbish dump.

The resources we use create waste so what do we do with this waste matter? We are responsible for the waste we produce and where it ends up.

The adult’s key role is to facilitate discussions during this activity or project, and assist the young people with access to documentation and other adults who may be able to assist with the planning of the event.

*For introduction and initial brainstorm activity.

Soil is a vital non-renewable resource. Nutrient rich soil gives us clean air and water, bountiful crops, diverse wildlife, healthy forests and landscapes. In this activity we will get our hands dirty to understand how soil texture influences the moisture holding capacity of different soils.

Soil preparation and collection before commencing this activity will assist in the time allocation of the activity.

Water is the most common substance found on earth and less that 1% is available as fresh water. Yet all plants and animals need water to survive. We need to conserve and protect fresh water resources. The Every Drop Counts learning activity explores the many ways that water is used, how you can reduce your water usage and reuse water.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

Spring is here; the sun is out and shining so it’s time to get sowing! Plant a seed and watch your little gem grow into a seedling and then into a tasty treat ready for harvesting.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

With Australia’s changing climate we need to adapt to our altering conditions. This is challenging but also possible for humans through behaviour change and infrastructure change, for example how we design our homes, farms and cities. It is not quite so easy for our precious wildlife. In this activity we can help support the needs of wildlife by giving them access to water year round.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

To increase your chances of observing beneficial insects carefully consider the suitability of the observation site and the current conditions. Optimal conditions for bee observations:

- an area that is home to native and exotic flowering species

- area protected from strong winds

- an open sunny location

- a warm location with temperatures above 20⁰ C

- between 10am and 2pm when the flowers open up wide to invite the bees in.

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

To increase your chances of observing animals carefully consider the suitability of the observation site and the current conditions. Consideration for animal observations:

- an area that has varied surfaces (sand, dirt, rocks, water bodies) and vegetation (grasses, high and low plants, shrubs, trees)

- rain, snow or wind may send some animals into hiding

- the time of day will determine the types of animals observed, e.g. nocturnal, crepuscular species may be sleeping or inactive during the day

- listen while you go searching, some animals make calls and will alert you to their location

*Time allocation will be dependent on site selection and travel time.

In this activity, you will invite your learners to connect with the natural features in your area – this could be in your schoolyard, eco-garden, local bushland or park etc.

The activity has been designed to help children think about why the land, the flora and fauna is important to them – and to identify a small action they can take to help protect, improve or enhance their local environment. Finally, this activity encourages learners to share their letters with a wider audience and promote caring for and protecting the environment on an ongoing basis.

If you need some inspiration, you can watch this video of Junior Landcare ambassador, Costa, speaking with students about why they love the environment and steps they are taking to care for it.

Checklist

- Outside drain (100g soil/dirt or clay , 100g leaves, twigs or sticks, plastic )

- Kitchen Sink (100ml of vegetable oil, 100g Organic food scraps)

- Kitchen Sink (20ml detergent)

- Toilet (4 squares of toilet paper)

- Toilet (2 x tissues)

- Toilet (2 x wet wipes)

- A tablespoon of soil/dirt

- 5 – 10 broken pieces of twigs or sticks

- A teaspoon of clay in water

- A teaspoon of chocolate drink powder

- 3 drops yellow food colouring and 1 square of toilet paper

- 10 sultanas

- Tablespoon of detergent

- 10 small rocks

- 5 small pieces of aluminium foil scrunched in balls

- ¼ piece of A4 paper ripped in strips

- Small plastic bag cut into pieces

- Tablespoon of vegetable oil

- Tablespoon of charcoal

- 20cm of plastic string or fishing line

- Tablespoon of sand

Instructions

STEP 1

STEP 1

Choose a seed to sow that is suited to your climatic zone and one that will produce fruit, vegetables or herbs for you to eat. Your seed packet will explain the best time to sow seeds.

STEP 2

STEP 2

Make a newspaper seed starter pot for your seedling. Tear a single sheet of newspaper in half and fold into thirds. Wrap the paper around an empty can but not too tight. Secure with tape on the side of the cylinder. Fold the paper down onto the base of the can, secure the flaps with tape. Slip your newspaper pot gently off the can. Make sure to use biodegradable or paper-based tape (e.g. masking tape).

STEP 3

STEP 3

Fill the seed starter pot two-thirds full with seed raising or potting mix. Carefully place your seed into the centre of the pot to a depth suitable for the specific seed and then cover with a thin layer of potting mix.

STEP 4

STEP 4

Your seed will need the right amount of water to germinate. Keep the soil in your seed planter pot soil moist by misting with a spray bottle every morning until it is time to plant in the ground or into a larger pot.

Step 1

Step 1

Why bees matter: Discuss the important role bees play in pollinating flowering plants and shrubs. As pollinators bees carry pollen from flower to flower to help the flowering plants make seeds, reproduce and make new plants. Bees help to grow our food. Without pollinators such as bees animals and humans would be without seeds, nuts and fruits to eat.

What makes other insects beneficial: Discuss the role insects play as decomposers, pollinators and as a food source for insectivores.

Step 2

Step 2

Outline safety aspects to the children, when observing insects.

Do not touch any insects, be gentle and quiet observers.

Instruct how to use tweezers, paintbrushes, tongs and garden trowels.

Guide the children to tread lightly, taking care not to stand on anything living while exploring. Ask the children to return things back to how they found them, e.g. turned rocks or logs.

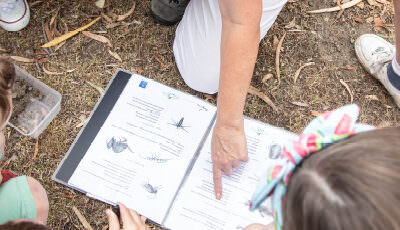

Examine your chosen field guide with the children (device or printed version) prior to exploring outside. Point out a beneficial insect they are likely to observe and model how to use the field guide.

Step 3

Step 3

Head outside to your observation site for a minimum of 7 minutes. Insects are everywhere but finding a spot near a garden bed or away from asphalt will allow children the opportunity to do some light digging. Allow children time for ‘slow looking’ in a micro environment. Encourage the children to explore the site Allow children time for ‘slow looking’. Encourage the children to explore the site, carefully looking at different locations using their senses to lead them. Carefully look at flowers to see if there are any active bees or other flying insects. Encourage the children to gently turn over the topsoil, bark, small rocks and leaf litter looking for ground dwelling insects.

If the children are successful at spotting an insect, see if they can attempt to identify the insect using their field guide.

Step 4

Step 4

Use the activity sheet to encourage the children to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations during and after the activity.

Step 1

Step 1

Predict which animals you might expect to see at your observation site, and which ones you might not expect to see?

Predict where in the habitat you might expect to see animals? Discuss locations in the habitat: in the air, on plants, in trees, under rocks, in the soil. Animals can be observed at different heights.

Step 2

Step 2

Examine your chosen field guide with the children (device or printed version) prior to exploring outside. Point out an animal they are likely to observe and model how to use the field guide.

Safety steps:

- outline safety aspects to the children, when observing animals

- be gentle and quiet observers. Do not touch any insects

- instruct how to use tweezers, paintbrushes, tongs and garden trowels

Guide the children to tread lightly, taking care not to stand on anything living while exploring. Ask the children to return things back to how they found them, e.g. turned rocks or logs.

Step 3

Step 3

Head outside to your observation site for a minimum of 7 minutes. We can find animals or traces of animals everywhere we go. Allow children time for purposeful observations, exploring the site, carefully looking at different locations and using their senses to lead them.

- Start by looking at the ground, get down low and guide the children to tread lightly. Use the trowels to gently move the soil, leaves and bark and magnifying glasses to examine small creatures up close. Remind the children to return things back to how they found them, e.g. turned rocks or logs.

- Stand up and see what you can find, taking care not to stand on anything living while exploring animals at eye height. Examine the leaves on bushes, flowers and bark on tree trunks.

- Look up high now, into the tall trees and the sky above. You might like to use binoculars to get a closer look at what is living above.

Step 4

Step 4

Use the activity sheet to encourage the children to make careful observations and thoughtful observations.

You might like to take photos instead to capture your observations.

Step 1

Step 1

Why bees matter: Discuss the important role bees play in pollinating flowering plants and shrubs. As pollinators bees carry pollen from flower to flower to help the flowering plants make seeds, reproduce and make new plants. Bees help to grow our food. Without pollinators such as bees, animals and humans would be without seeds, nuts and fruits to eat.

What makes other insects beneficial: Discuss the role insects play as decomposers, pollinators and as a food source for insectivores.

Step 2

Step 2

Examine your chosen field guide with the children (device or printed version) prior to exploring outside. Point out a beneficial insect they are likely to observe and model how to use the field guide.

Outline safety aspects to the children, when observing insects.

- Be gentle and quiet observers. Do not touch any insects.

- Instruct how to use the garden trowels or spoons and paddle sticks or paintbrushes.

- Guide the children to tread lightly, taking care not to stand on anything living while exploring.

- Ask the children to return things back to how they found them, e.g. turned rocks or logs.

Step 3

Step 3

Head outside to your observation site. Insects are everywhere but finding a spot near a garden bed or away from asphalt will allow children the opportunity to do some light digging.

Allow children time for ‘slow looking’ in a micro environment. Encourage the children to explore the site, carefully looking at different locations using their senses to lead them.

Carefully look at flowers to see if there are any active bees or other flying insects. Use the trowels or spoons to gently turn over the topsoil, bark, small rocks and leaf litter looking for ground dwelling insects. Using the paddle sticks or paintbrushes, attempt to move the insects into the plastic container to observe.

If the children are successful at spotting an insect, see if they can identify the insect using their field guide.

Step 4

Step 4

Use the activity sheet to encourage the children to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations during and after the activity.

You might like to take photos to capture your observations.

Step 1

Step 1

Why bees matter: Discuss the important role bees play in pollinating flowering plants and shrubs. As pollinators bees carry pollen from flower to flower to help the flowering plants make seeds, reproduce and make new plants. Bees help to grow our food. Without pollinators such as bees animals and humans would be without seeds, nuts and fruits to eat.

What makes other insects beneficial: Discuss the role insects play as decomposers, pollinators and as a food source for insectivores.

Step 2

Step 2

Outline safety aspects to the children, when observing insects.

Do not touch any insects, be gentle and quiet observers.

Instruct how to use tweezers, paintbrushes, tongs and garden trowels.

Guide the children to tread lightly, taking care not to stand on anything living while exploring. Ask the children to return things back to how they found them, e.g. turned rocks or logs.

Examine your chosen field guide with the children (device or printed version) prior to exploring outside. Point out a beneficial insect they are likely to observe and model how to use the field guide.

Step 3

Step 3

Head outside to your observation site for a minimum of 7 minutes. Insects are everywhere but finding a spot near a garden bed or away from asphalt will allow children the opportunity to do some light digging. Allow children time for ‘slow looking’ in a micro environment. Encourage the children to explore the site Allow children time for ‘slow looking’. Encourage the children to explore the site, carefully looking at different locations using their senses to lead them. Carefully look at flowers to see if there are any active bees or other flying insects. Encourage the children to gently turn over the topsoil, bark, small rocks and leaf litter looking for ground dwelling insects.

If the children are successful at spotting an insect, see if they can attempt to identify the insect using their field guide.

Step 4

Step 4

Use the activity sheet to encourage the children to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations during and after the activity.

STEP 1

STEP 1

How do humans use water in our daily lives?

From morning to night we use water for drinking washing and cooking and contributes to our health. Water is an essential resource in our local environment, industry and agriculture. Discuss these concepts with the children. What other questions arise from this discussion.

Where does our drinking water come from?

The potable water we use comes from various sources depending on where you live in Australia. Water is obtained from rainwater and harvested in tanks and reservoirs, it comes from nearby streams, springs, rivers and lakes, from groundwater or desalination plants and is then treated.

Use the videos to help stimulate discussion and the journal activity sheet to draw or record highlights.

STEP 2

STEP 2

How can we responsibly share water with other living things?

Water is a basic need and right for humans and animals alike. Animals, like humans need water for their minds and bodies to function properly. They can become stressed and confused when dehydrated. Most animals do not store large quantities of water in their bodies in the same way humans do, so most need to drink regularly. Much of their water is found in the food they eat.

We have the ability to help other living beings when they are in need of water and are unable to source it themselves.

Due to lack of regular rainfall, low rainfall, drought or bushfires, water can become scarce for animals. Providing water is a simple yet effective way to help local fauna (animals).

Continue to use the journal to draw or record discussion highlights.

STEP 3

STEP 3

Find a shady location, bordered by high grasses, plants or shrubs in your outdoor space. Place the water container here; this will help hide wildlife hide from possible predators when drinking or bathing. Make sure it’s also in a location where you can easily access the container for cleaning and refilling and also observe any wildlife activity around the water.

When setting up your container add a rock or two to the base before covering with clean water. If the container is large you might also like to add a medium size branch to the container so that small animals such as skinks can climb in and out safely.

STEP 4

STEP 4

Top up water when the level appears low or the water becomes dirty. Intermittently observe the water container on warm or hot days. Predict and record which animals might visit your water container and at what time of day in your journal. Which is the smallest animal who could access the water? Which is the largest? Think about where you live, and what animals you have observed in the past.

If you feel the location is not optimal after observing and trialing the location of your water container move it to another location which might be more suitable for wildlife.

STEP 1

STEP 1

How do humans use water in our daily lives?

From morning to night we use water for drinking washing and cooking and contributes to our health. Water is an essential resource in our local environment, industry and agriculture. Discuss these concepts with the children. What other questions arise from this discussion.

Where does our drinking water come from?

The potable water we use comes from various sources depending on where you live in Australia. Water is obtained from rainwater and harvested in tanks and reservoirs, it comes from nearby streams, springs, rivers and lakes, from groundwater or desalination plants and is then treated.

Use the videos to help stimulate discussion and the journal activity sheet to draw or record highlights.

STEP 2

STEP 2

How can we responsibly share water with other living things?

Water is a basic need and right for humans and animals alike. Animals, like humans need water for their minds and bodies to function properly. They can become stressed and confused when dehydrated. Most animals do not store large quantities of water in their bodies in the same way humans do, so most need to drink regularly. Much of their water is found in the food they eat.

We have the ability to help other living beings when they are in need of water and are unable to source it themselves.

Due to lack of regular rainfall, low rainfall, drought or bushfires, water can become scarce for animals. Providing water is a simple yet effective way to help local fauna (animals).

Continue to use the journal to draw or record discussion highlights.

STEP 3

STEP 3

Find a shady location, bordered by high grasses, plants or shrubs in your outdoor space. Place the water container here; this will help hide wildlife hide from possible predators when drinking or bathing. Make sure it’s also in a location where you can easily access the container for cleaning and refilling and also observe any wildlife activity around the water.

When setting up your container add a rock or two to the base before covering with clean water. If the container is large you might also like to add a medium size branch to the container so that small animals such as skinks can climb in and out safely.

STEP 4

STEP 4

Top up water when the level appears low or the water becomes dirty. Intermittently observe the water container on warm or hot days. Predict and record which animals might visit your water container and at what time of day in your journal. Which is the smallest animal who could access the water? Which is the largest? Think about where you live, and what animals you have observed in the past.

If you feel the location is not optimal after observing and trialing the location of your water container move it to another location which might be more suitable for wildlife.

Step 1

Step 1

If your location does not have a food garden, creating a vision will help to plan and achieve the best possible results.

In your research phase, find out more about successful food gardens.

Read more about a Junior Landcare case study that focuses on food production. Use the filters for topic and content type to search for a suitable case study to understand more about what can be achieved.

Research and discuss:

- the set up and steps involved

- the benefits

- the challenges

- special ideas.

STEP 2

STEP 2

Creating the food garden vision.

- Ask the children what are the benefits of creating a food garden in our local area?

- Discuss the benefits for sustainability, health, learning, expenses and your community.

- What do you think will make your food garden a success?

- Who else can we involve?

You want the best possible outcome, therefore it is ideal to involve as many people as possible in your decision making process. This will help promote ownership and future interest in the food garden.

At a school, this could include interested students, the groundskeeper, volunteers and any other keen participants.

At home, it is good to have a family discussion to focus on what you would really like. Use your research for inspiration.

STEP 3

STEP 3

Discuss in small groups:

- who will be responsible

- what resources will you need?

- where can you grow food?

- how big will your food garden be?

What is your food garden vision? What are your goals and your creative ideas? What gets you excited about your planned food garden?

Use the activity sheet to record ideas.

STEP 4

STEP 4

After completing the activity sheet, have the children discuss their ideas and vision with each other.

In the discussion consider:

- limitations and restrictions

- who might be able to help?

- what equipment might we need?

- what budget is required?

Once you have discussed and agreed on your vision, you can go to the next stage of the creating your food garden learning activity.

Step 1

Step 1

Mapping and understanding your local space will help you explore the possibilities and decide the best location for creating a food garden.

Begin discussion by exploring what plants need to grow in your food garden. Include discussion around water, light and soil.

Gather any background information including other maps to help your discussion.

Where is the best location for our food garden?

Explain that we will be exploring the grounds to determine what the best location might be for a food garden.

To determine the best location for the food garden, account for the access to water, sunlight and shade, and that many plants do not like to grow in windy areas.

Step 2

Step 2

Define the areas you will explore together and distribute the printable activity sheets, pencils and clipboards. Children can work in groups.

If you have existing site maps, refer to it so that can point out north and other directions. Use the compasses to orient where north and south is and refer to it on your map/s.

Ask children to use their observation skills to look closely at their environment to understand it more.

You might like to take photos to capture your observations.

Step 3

Step 3

With the resources ready, conduct a walk around your grounds to assess each location.

Consider the size and shape of your food garden, noting it is a good idea to start small.

Children will use their observation skills to assess, map, label and photograph:

- location of buildings and other features

- location of water sources

- visibility – a location that people will see regularly

- ease of access for garden helpers

- drainage

- shade

- wind

- soil types

- safety.

Complete the activity sheet with your observations for each identified site.

Step 4

Step 4

Review each activity sheet and discuss locations to determine the best location for your food garden.